proposal

Keeping your mind right as a black woman in a discriminatory world that is also politically and physically crumbling is difficult. Sometimes the best thing wecan do for ourselves is rest.

My project, ‘The Time to Rest is Now (Not When You’re Dead)’ explores the relatively new and radical idea of understanding rest as a form of resistance against a violent world that exploits everyone for capitalist profit, but particularly disadvantages black women in western societies who struggle to deal with the mental toll of ‘mutually

interlocking’ systems of ‘capitalism, colonization, racism, and

heteropatriarchy’.[1]

I first became interested in this idea through The Nap Ministry, a social

movement dreamt up by Tricia Hersey, a ‘teaching artist, chaplain, poet, theatermaker, performance artist, and community organizer’.[2] I discovered her liberatory anti-capitalist philosophies via Twitter. Through social media, I started to become aware of growing discontentment amongst young people about the evident pointlessness of labouring in broken western economies for pay cheques that do not cover our essential needs and leave us stressed and still wanting. These online conversations prompted me to reflect on my own experience of working for an exploitative and uncaring company, and how the traumatic experience affected my value system.

I began this project as a mental health exercise, intending

to use photography to connect with others who related to my experiences or

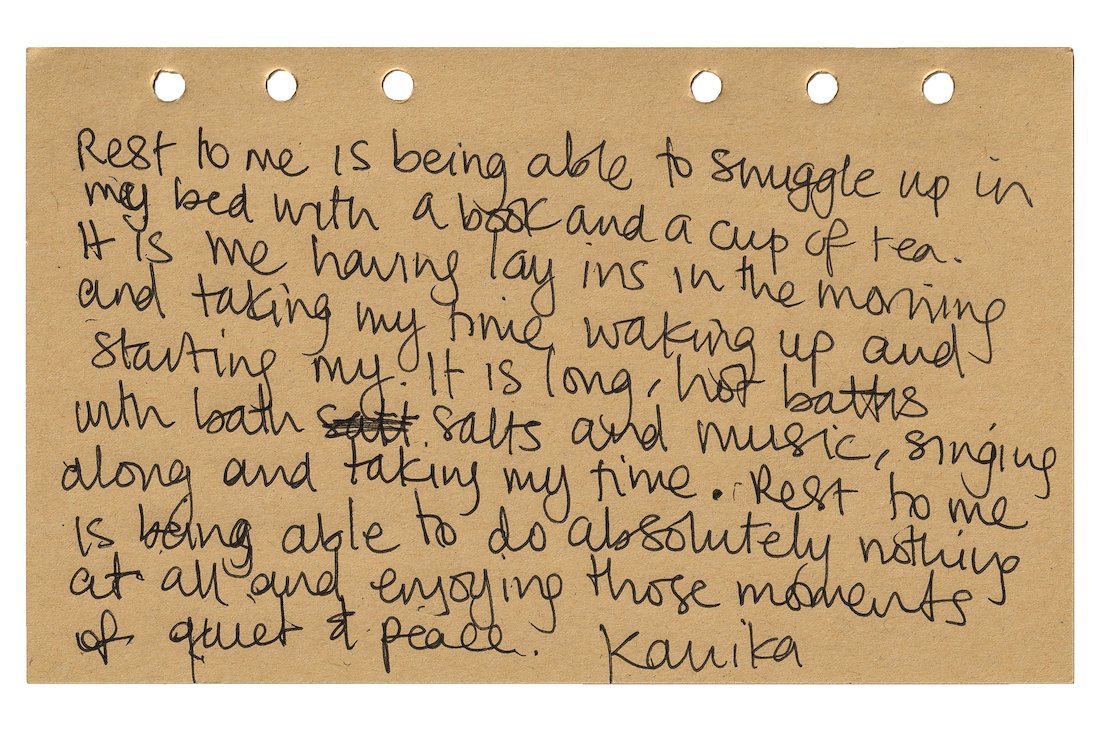

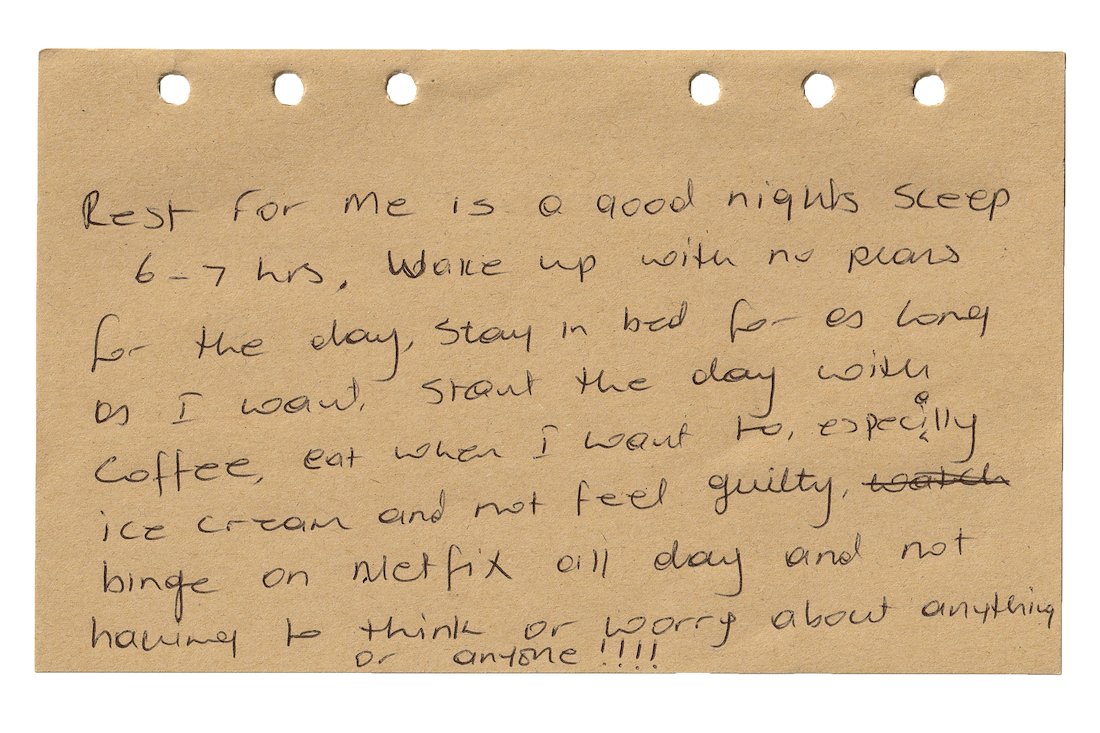

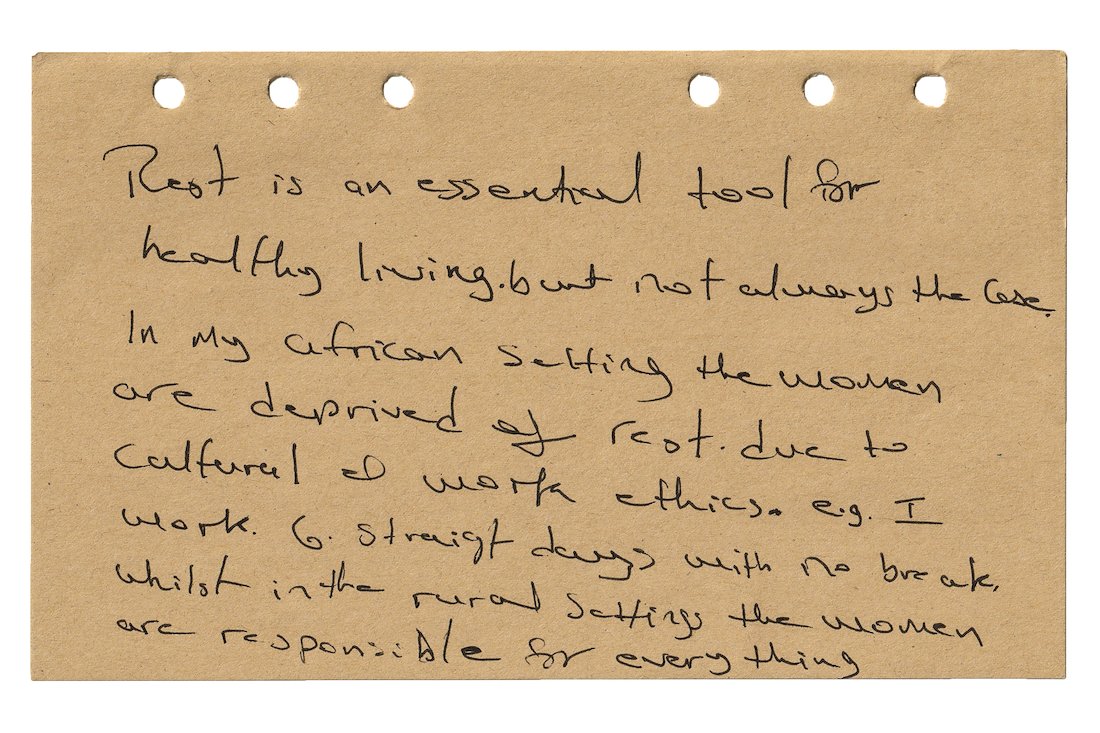

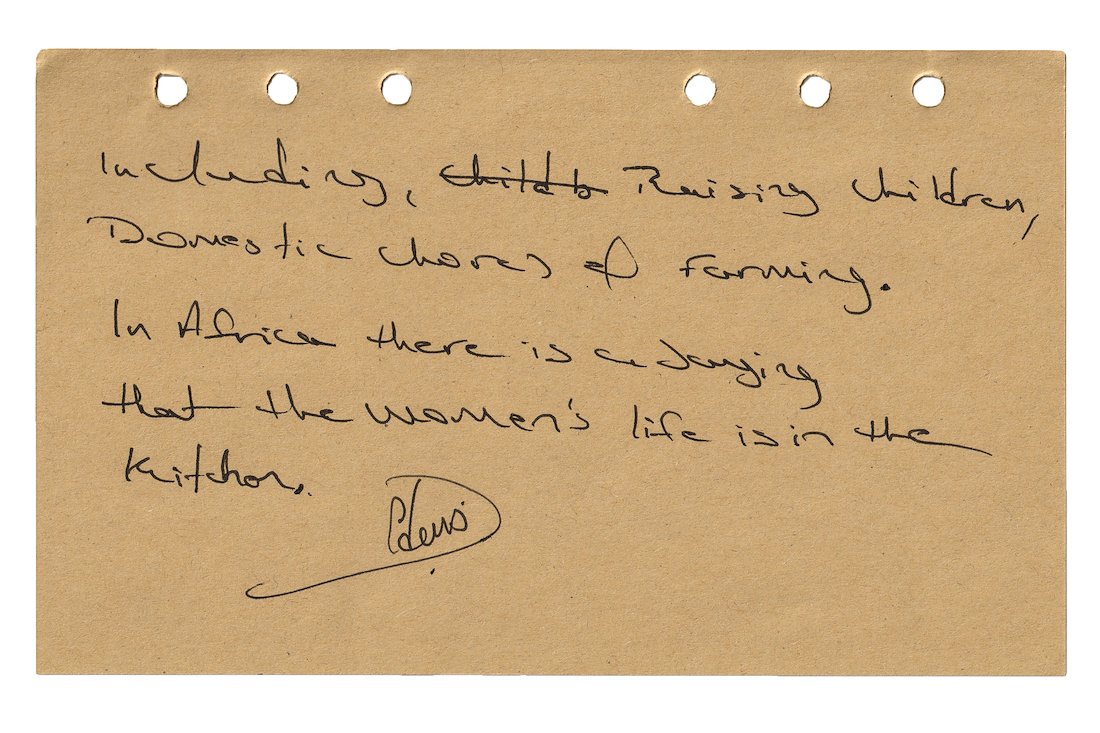

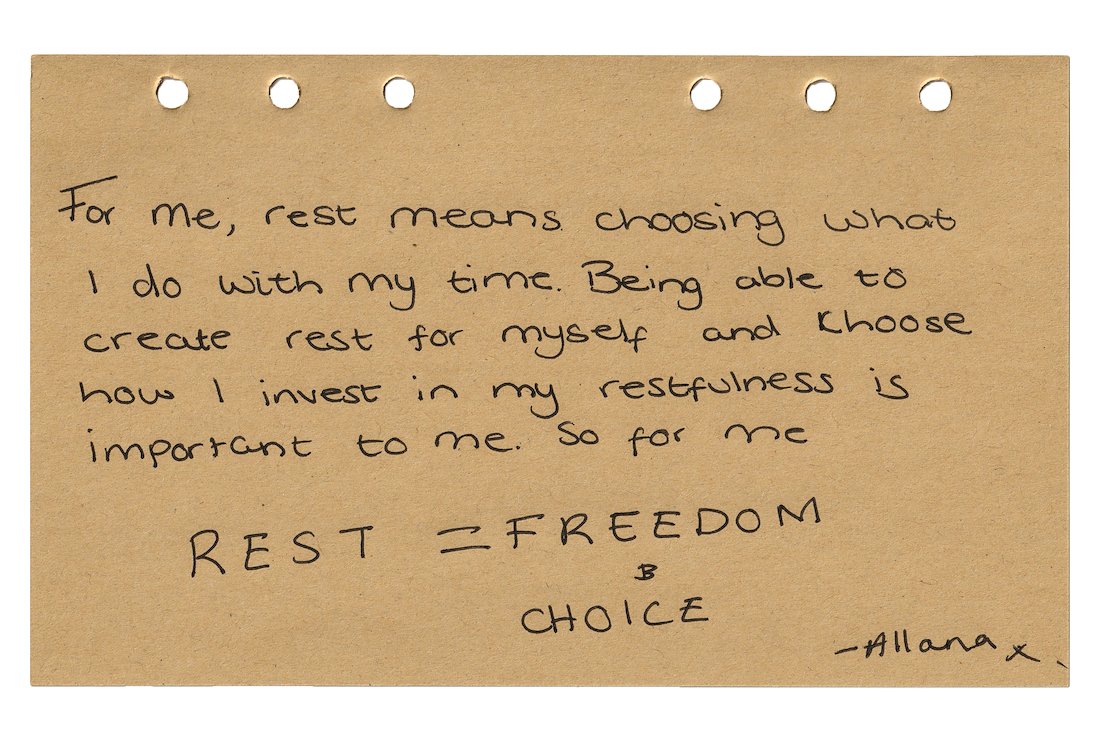

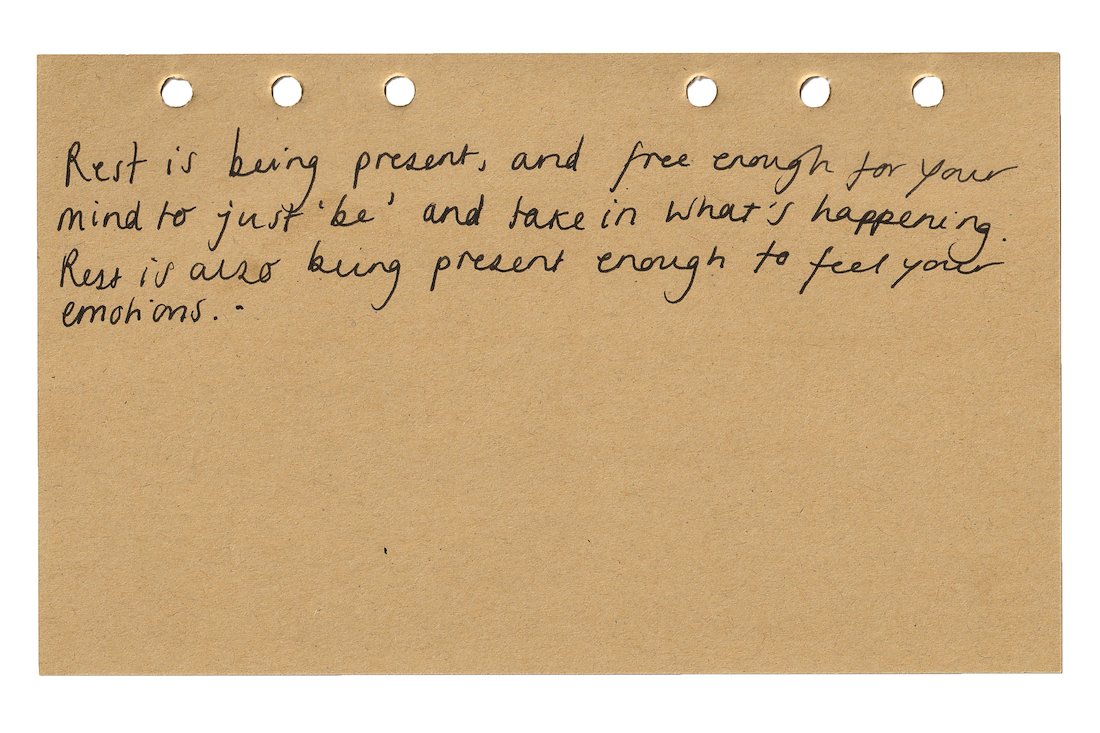

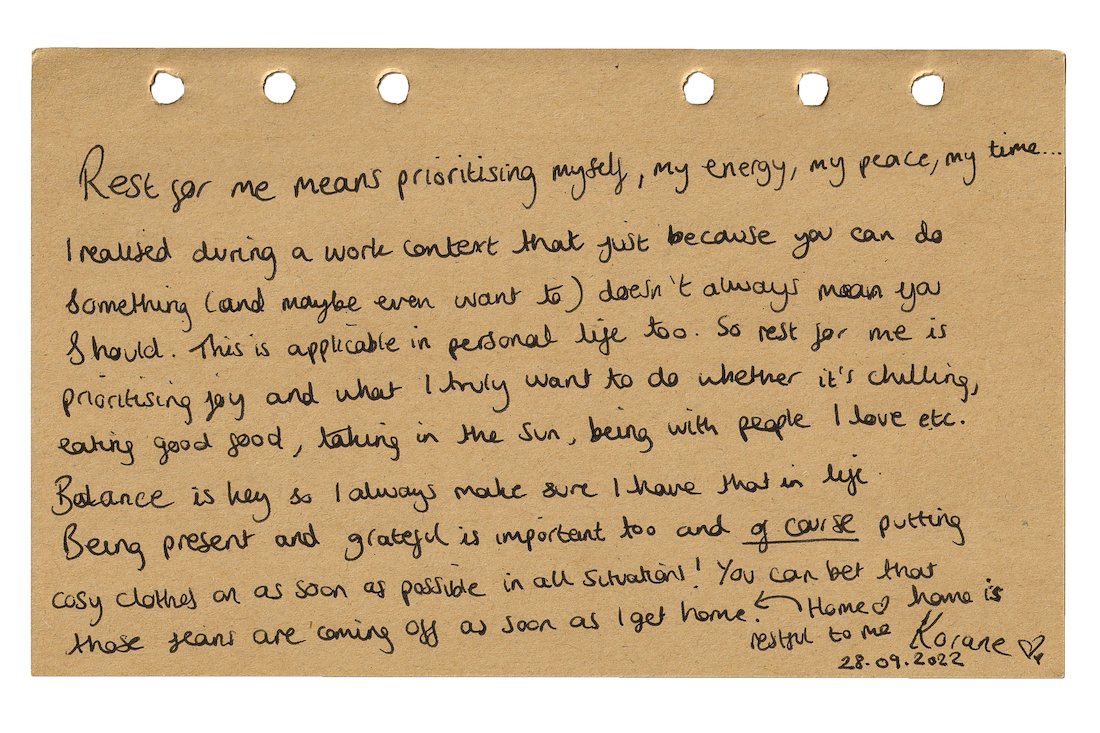

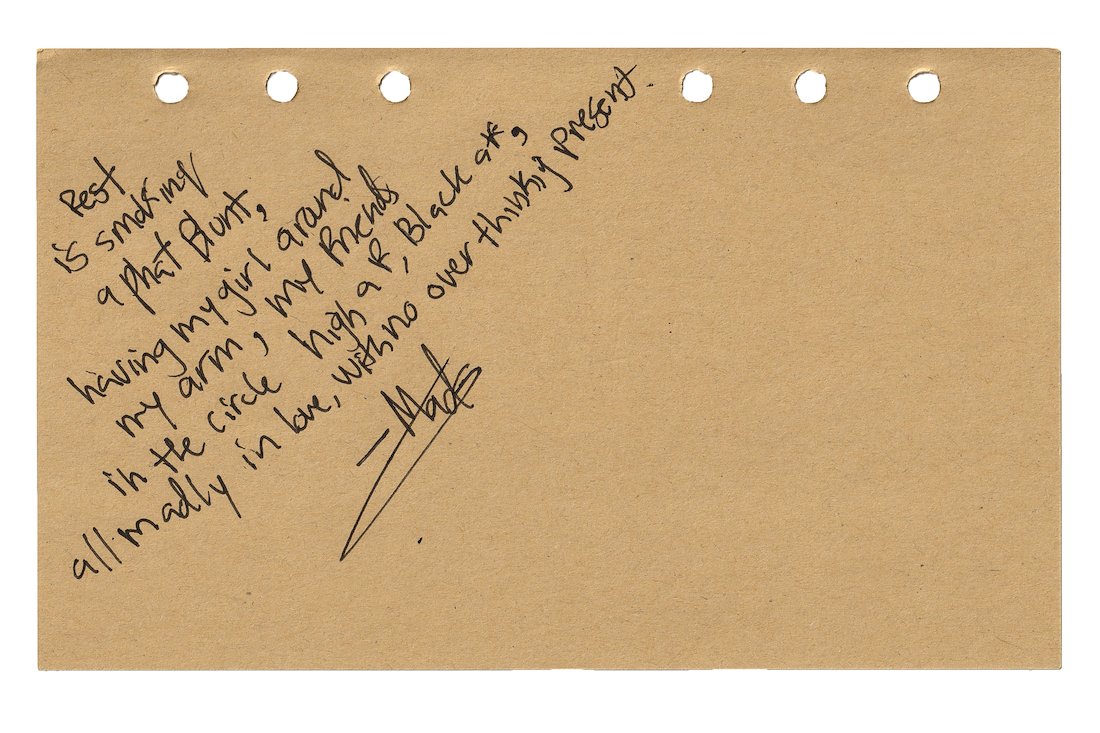

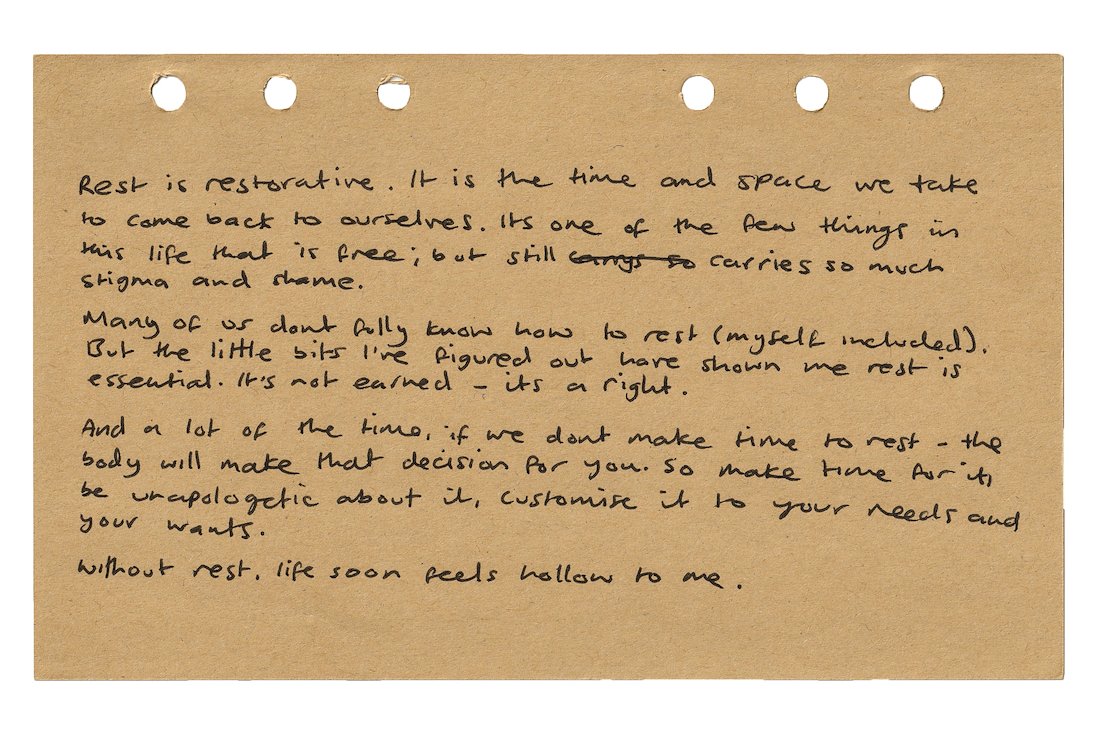

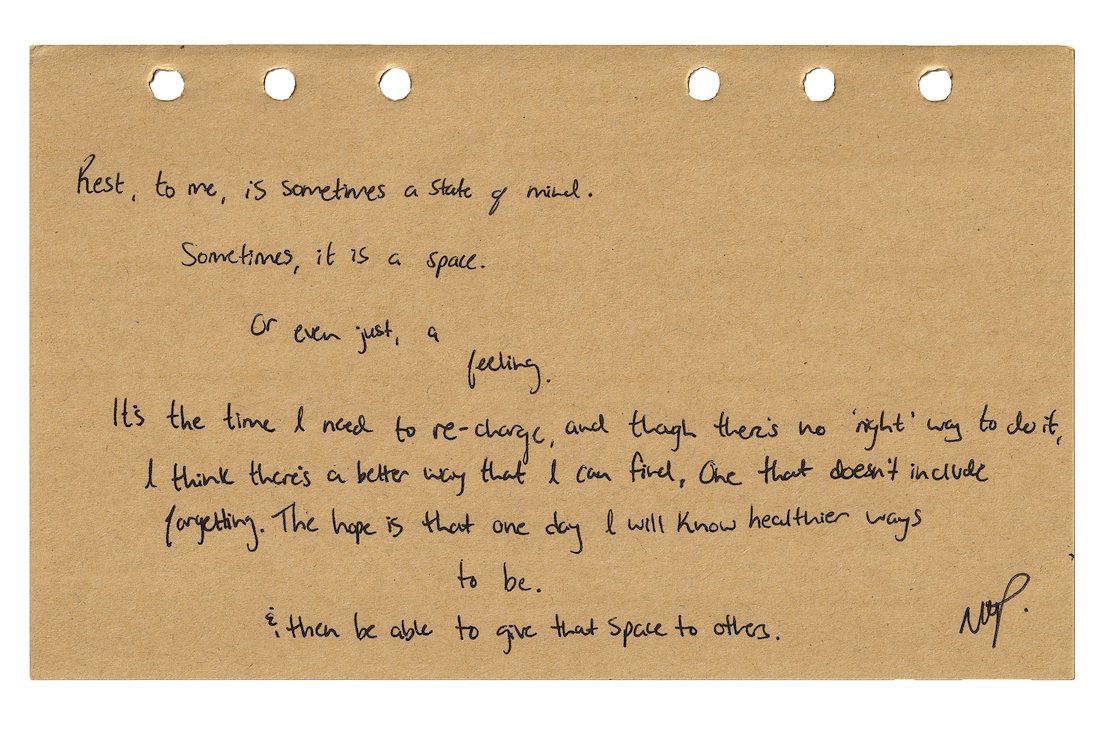

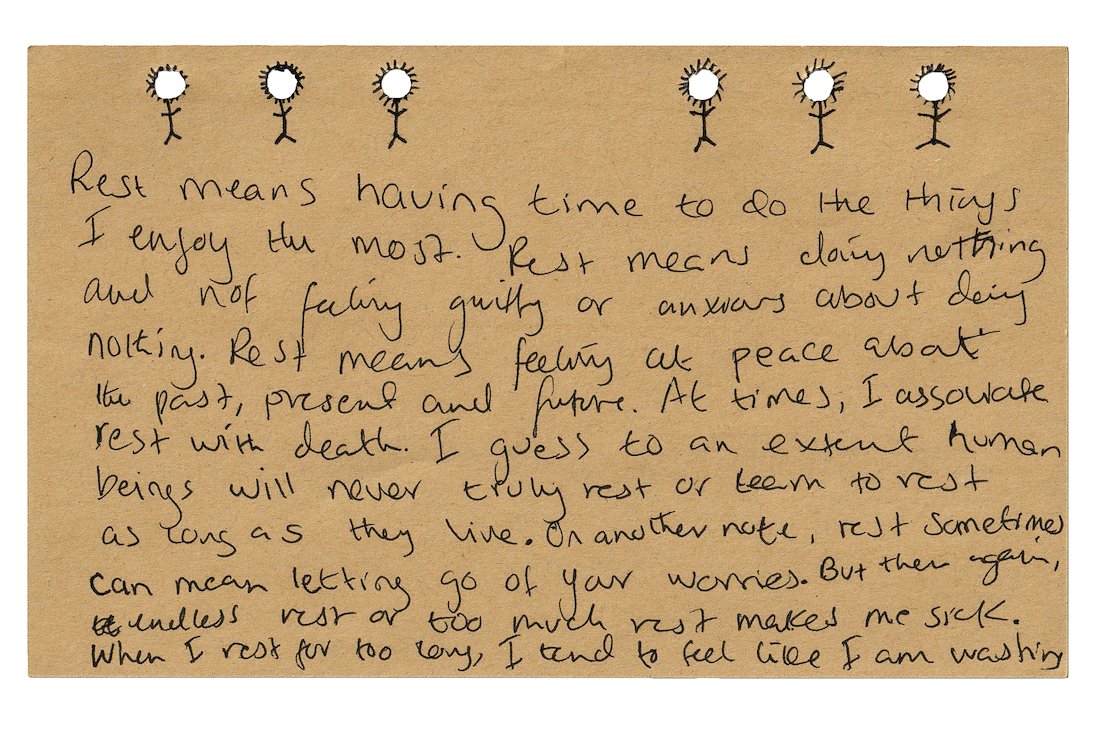

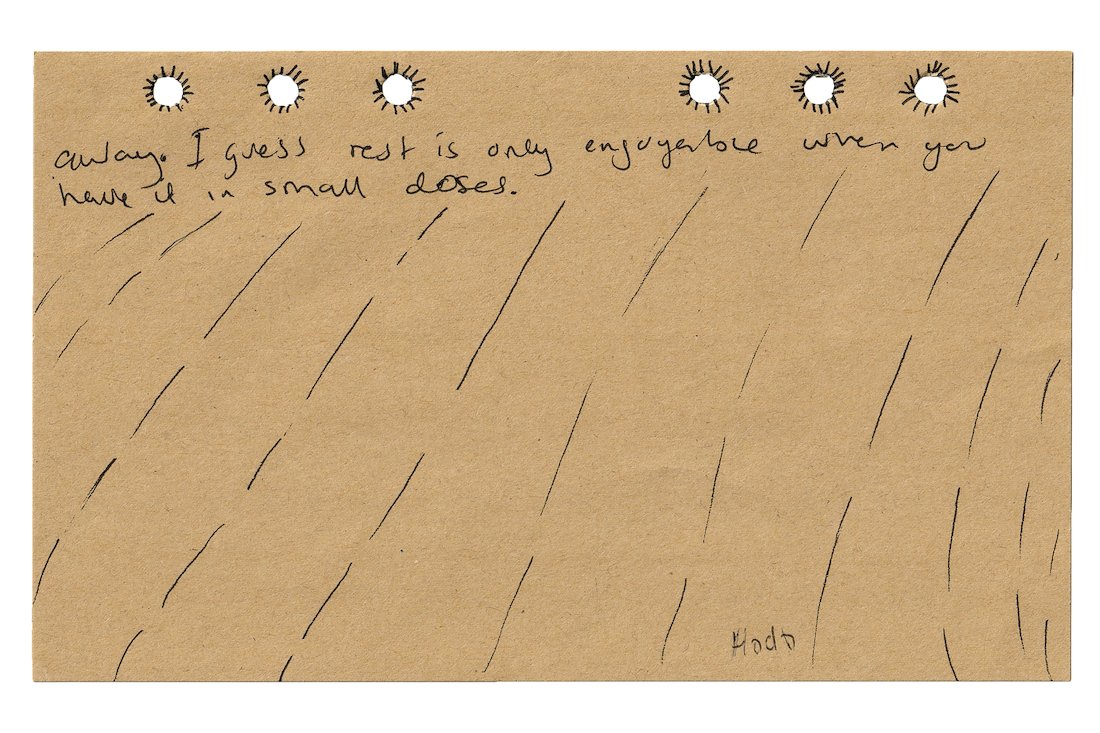

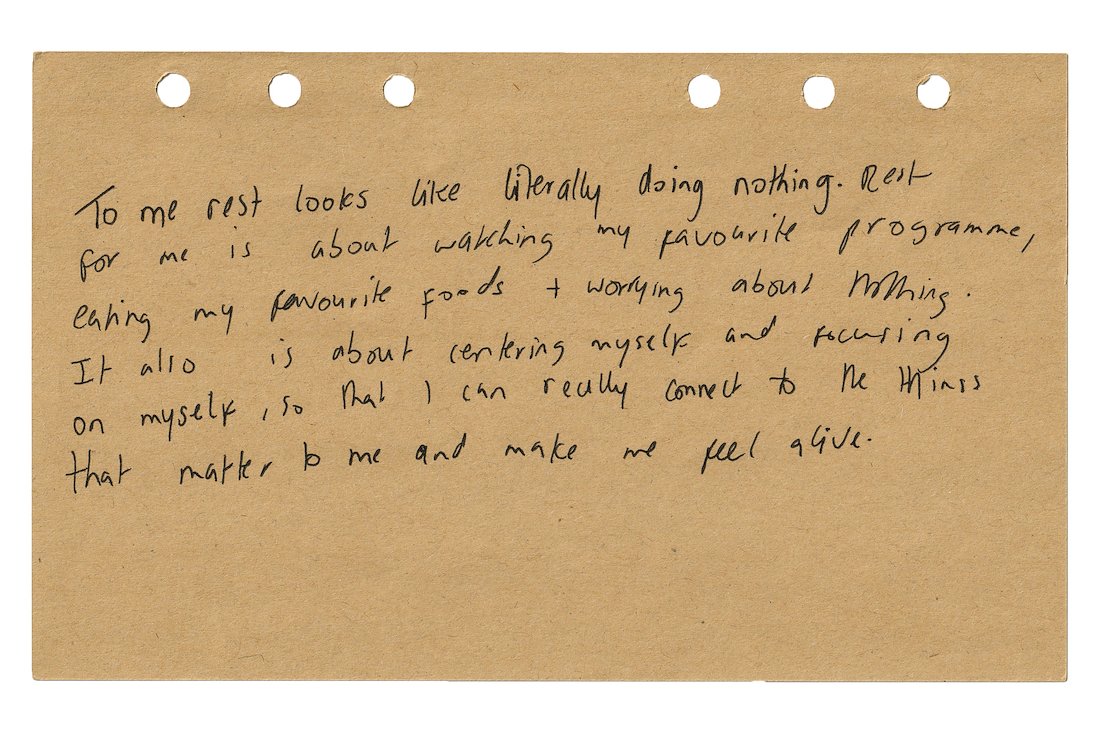

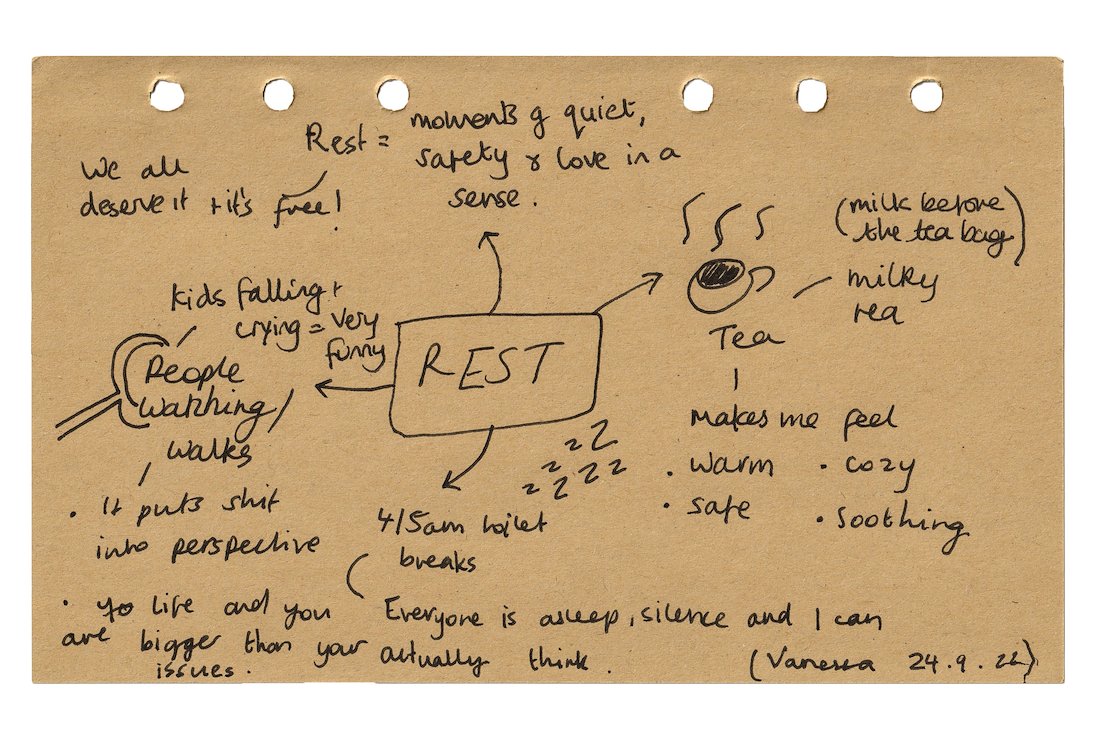

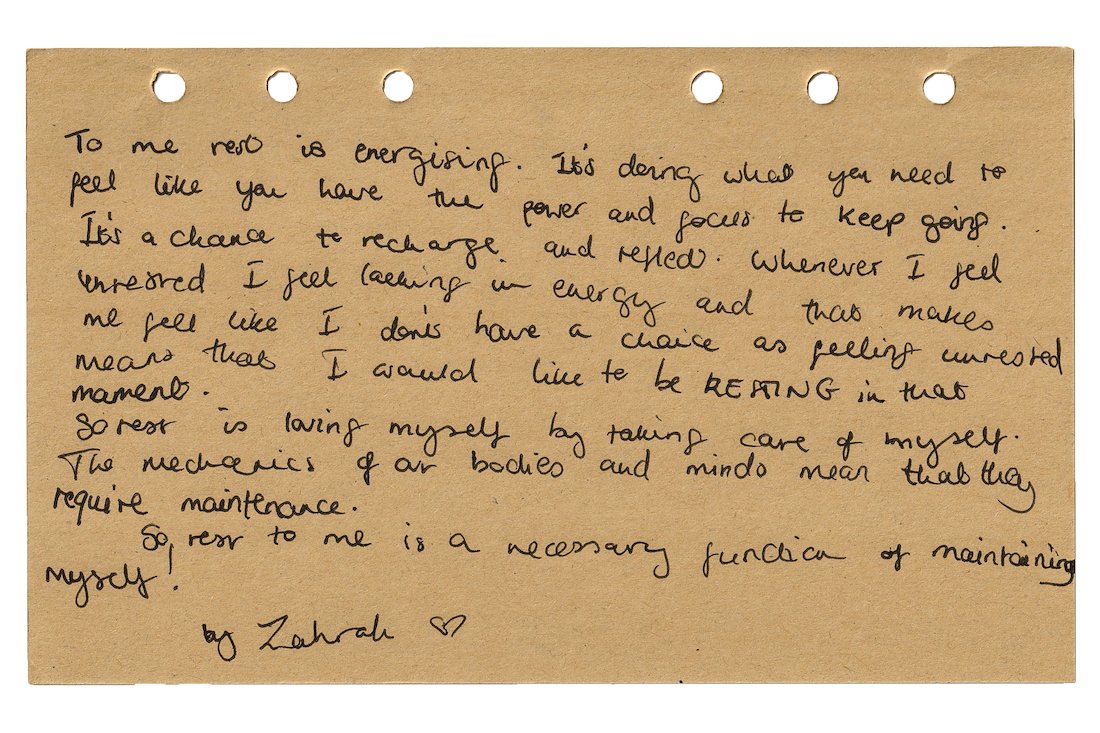

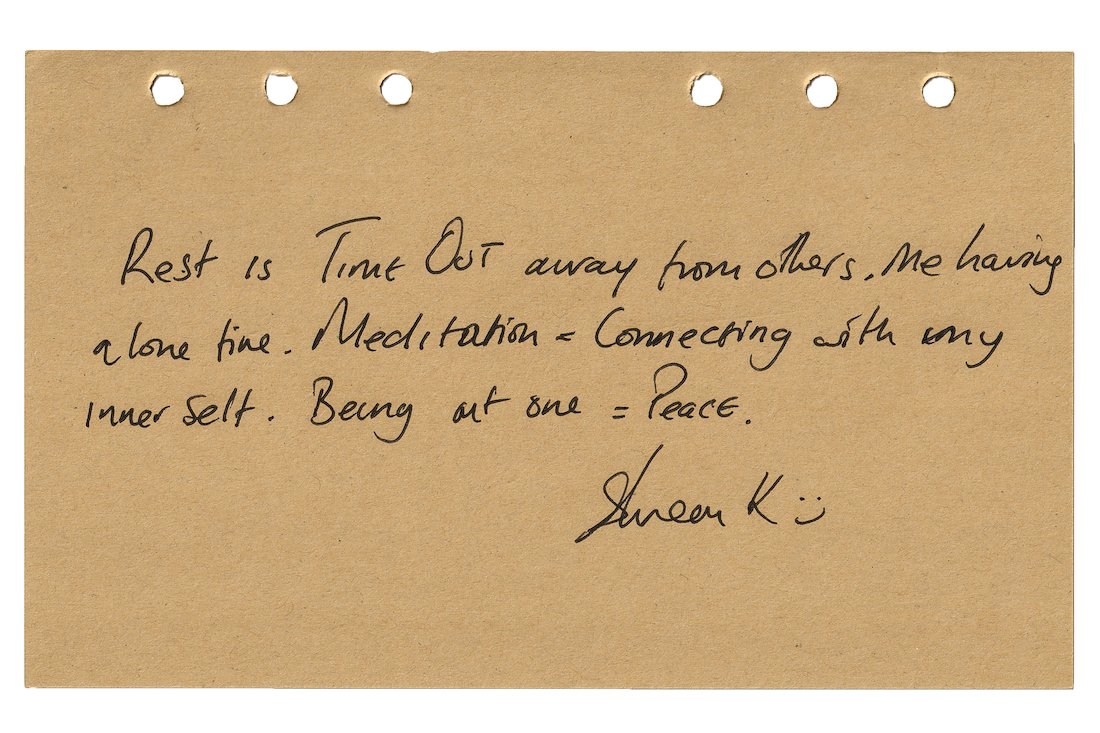

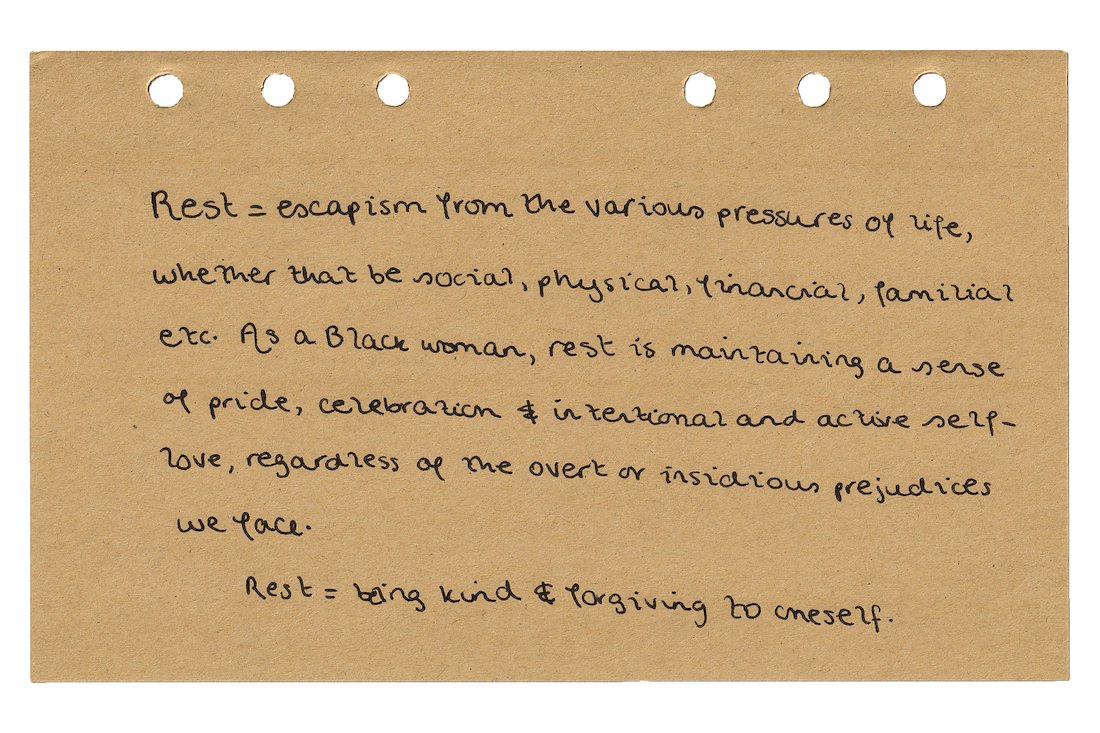

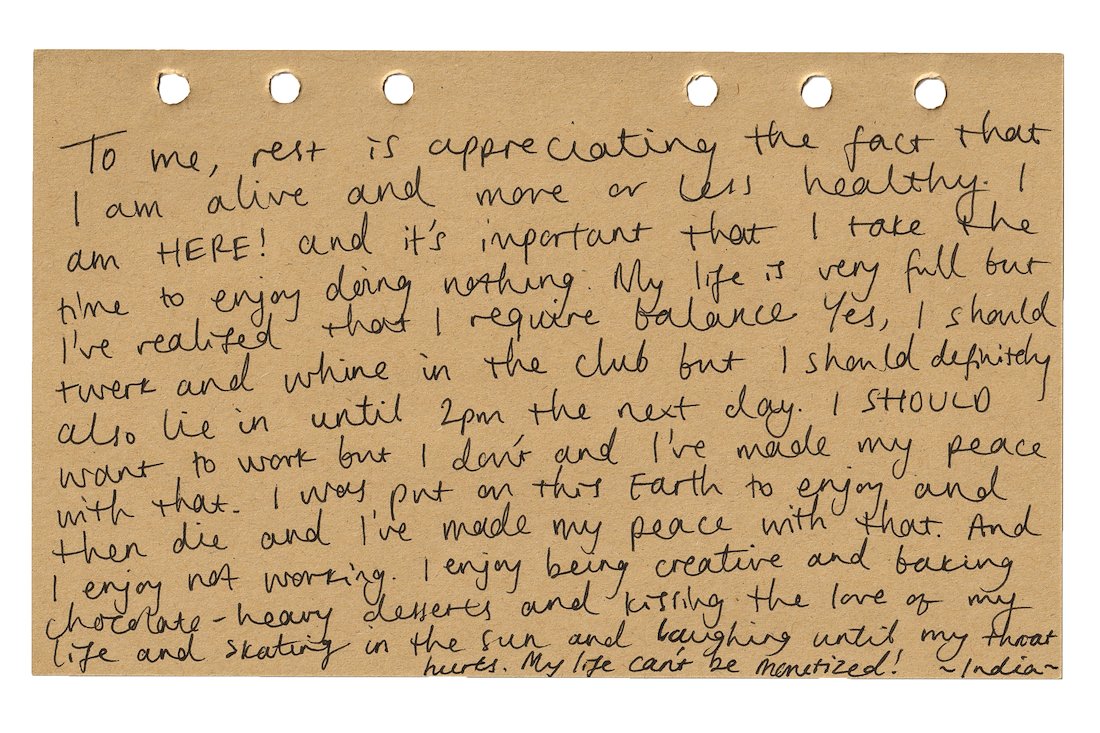

perhaps had a very different relationship to work and rest. The process of interviewing fifteen black women, all friends or family, was deeply therapeutic. I sought to find out how these women’s beliefs had been shaped by their upbringing, how their beliefs had perhaps shifted once they started working, what forms of rest they engaged in and how rest made them feel. I considered it important to encourage people I know and love to embrace rest as part of their everyday lives instead of entertaining the idea that they could rest when they were dead.

I sought to document black women at rest instead of at work, both through images and text made up of their written and transcribed words. I wanted to create a project that reflects how black western women feel about doing nothing in the wake of lockdowns, protests against institutional racism and an ongoing cost of living crisis, moving beyond the sometimes restrictive lens of ‘black joy’ which is valuable and relevant but still relies on black people expending energy.

It was a pleasure to create my final scrapbook made up of interviews, photographs, notes and personal diary entries with my own

two hands. It was a labour of love. And labour, I did. But in doing so I fully gave myself the space to be childish and entertain simple pleasures. This project truly forced me to incorporate abundant and restorative rest into my life, even as a freelancing creative balancing several part-time jobs and trying to make a living in London. Choosing to rest in an environment that would rather you were a machine is undoubtedly an act of resistance.

[1] V, Francoise. (2021) A Decolonial Feminism. London: Pluto Press, p. xii.

[2] Tricia Hersey (2022) About. Available at: www.triciahersey.com/about